Material Conditions: How the Cage Changes MMA

"[People] make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living." – Karl Marx, 1852

The cage changes everything. The cage is more than a physical structure, it's the material conditions that shape the behavior and performance of a fighter. Martial art movements, like any other movement, require room—just as generating power requires room. The cage allows for movement but also limits it. Even in the center of the cage, where there's open space, the cage still creates a sense of confinement and pressure. Since the focus of a fight is on the two competitors, the environment might seem trivial, but in reality, the environment shapes the fight. The environment shapes everything.

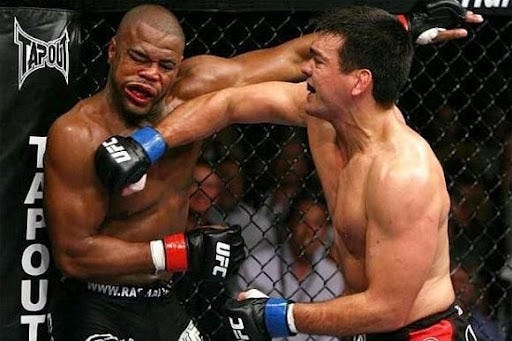

When former UFC champion Rashad Evans faced future UFC champion Glover Teixeira on April 16, 2016, he was knocked out within the first two minutes of the first round. Evans was fast and agile in open space but had a tendency to walk into the fence, forcing himself into a defenseless square stance.

The cage is physical but also symbolic and psychological. Fighters know they shouldn't back themselves into the fence and how to get away when they do, but sometimes it's just the daunting experience of being in the cage.

If composure slows time, then emotional arousal and anxiety do the opposite, which can negatively affect a fighter's performance and decision-making.

Evans was caught in a vice, with the cage on one side and Teixeira on the other. Physically and psychologically pinned, Evans was open for strikes and limited in his movement. His physical advantages were negated. For Teixeira, the cage was a source of motivation and confidence. The end was academic, as the heavy-handed Glover Teixeira caught Rashad Evans with a bone-crushing left hook.

The material conditions of the cage turn mixed martial arts (MMA) into a game of advantages vs. limitations. Understanding your conditions is the difference between knowing you have to hold your breath in water and not knowing you're in water.

On May 23, 2009, Lyoto Machida beat Rashad Evans for the UFC light-heavyweight title. The pattern was the same: Evans was backed up against the cage and knocked out.

Against the fence, offense and defense are nullified. The unyielding surface of the cage acts as a baking board as your opponent pin-rolls you upright. You conform to the shape of the cage, rigid and flat. The material conditions of the cage not only shape behavior but also shape you. The cage is not only a physical structure but a superstructure, both a visible and invisible framework.

The material conditions reveal themselves even in fights Evans has won or lost by decision.

On January 2, 2010, Evans was hurt along the fence against Thiago Silva but managed to survive and gut out a decision.

On June 9, 2018, Evans was on the other side of the cage against Anthony Smith. But instead of opening up with punches, he clinched Smith, turning his advantage into a 50/50 position. Neither Smith nor Evans had space to operate. Since both were caught in a vice, the only movement available was up and down. Evans put his head down while Smith threw his knee up.

Smith stayed composed, Evans stayed tense. Speed can compensate for a lot, but against the cage, there is no speed.

There are multiple opponents in the cage. There's the formidable opponent before you, the unyielding fence behind you, and the unforgiving surface beneath you. The tensions build to a boiling point when you, the cage walls, and the fighting surface converge. You're caught between a rock, a hard place, and an even harder place.

Once you step into the cage, you must be aware of your surroundings at all times, just as you should know where the boundaries and obstacles are in self-defense. This is why training in a cage is essential for MMA, and incorporating walls and obstacles is useful for self-defense.

To best understand the task at hand, you must best represent the task in your training. Only then can you anticipate the unpredictable, adapt to the demands, and manage your stress. Training with the barriers included best simulates real-life fighting conditions, whether a prizefight or self-defense.

On October 16, 1998, Vitor Belfort caught Wanderlei Silva with a left straight. Instead of clinching, shooting, or moving laterally, Silva instinctively ran backward. With nowhere left to go, he was pummeled against the cage.

Silva had no prior experience with the cage, neither in terms of training nor actual fights. The surroundings weren't something fighters put much thought into back then. They didn't understand how the cage would affect their spatial and tactical awareness, nor their ability to withstand punches.

Being punched against the cage is like being punched on the ground—it's your head against a hard surface. This is different from being hit in open space or against the ropes. Imagine throwing a walnut into the air and hitting it with a bat. The walnut will go flying. Place the walnut on a table and hit it again. The bat will smash the walnut to pieces. Does changing the environment change the outcome for the walnut? Absolutely. Just as going from Earth to space will change all the rules of physics you're used to. The conditions set the rules.

UFC legend and two-division champion Randy Couture used the cage as the linchpin to his offense. He roughed up younger and faster fighters by pinning them against the fence. On August 21, 2004, Couture wedged Vitor Belfort between the cage and the mat and bloodied him to a pulp to win back the light-heavyweight title. The cage played a material role in Couture's longevity against younger fighters.

Before the UFC, most martial artists trained as if they had unlimited space. (Due to tradition, this is still mostly true.) Even though gyms have walls, martial artists were used to resetting every time they got near a wall, unconsciously conditioning themselves to pretend they were fighting in an environment without borders. As a result, their training was nonrepresentative of reality.

Similarly, fighters used to fighting in the ring had difficulty transitioning to the cage.

Antônio Rogério Nogueira, a former Pride FC standout, was expected to become a contender for the UFC light-heavyweight title. However, Pride FC used a ring, not a cage. On paper, when he fought Anthony Johnson on July 26, 2014, it looked as though Nogueira would be the better striker. Johnson had power, but Nogueira had crisper boxing and was even a Brazilian national boxing team member. But is "better" about effectiveness or aesthetics? In a vacuum, Nogueira had straighter punches. But we don't fight in a vacuum, we fight in our surroundings. Anthony Johnson was better adapted for the cage. The better adapted fighter is the more skilled fighter. The better boxer isn't the one with prettier punches but the one better adapted to box in their environment. Anthony Johnson was the better cage boxer.

The fight lasted 44 seconds. Johnson traded with Nogueira, Nogueira walked himself into the fence, limiting his own movement, and was knocked out.

Takedowns are also easier along the cage walls, adding another dimensional threat: if you cover up, you get taken down; if you block the takedown, you get punched in the face.

However, since the fence holds you up and creates friction, fighters have adapted, using the cage to stand back up. But these developments can only happen if you train for the cage rather than a vacuum.

Performance is about preparation. Preparation is about education and learning. Consider how education is affected by the conditions and environment. Is learning only about information processing, or is it also about the environment? Materially, will telling a child how to use technology have the same result as a child who always has access to the best technologies? No. The first child doesn't have an information problem, they have a material problem.

Education demands a lot and requires more than just time spent in the classroom. Then how much of educational success is determined by how much of the demands can be met at home? Is it about trying harder and being told what you're lacking, or is it more the ability to replicate school and its demands in the home environment? A coach can give as much instruction as they want, but without access to a cage, their fighter is at a disadvantage. Likewise, having an environment to learn and the conditions to apply that learning is more important than educational instruction.

The conditions change the discourse.

In our daily lives, how often does the room change the conversation? Who has a better outcome, the one who reads the room or the one who doesn't?

The material conditions of the cage are dire, but so are the material conditions of our lives. Just as the outcomes of fights are determined by the conditions in which they take place, so too are our outcomes.

The cage is ultimately a metaphor for the larger economic and social forces that shape and constrain our behavior and agency. Just as fighters reflect their superstructure, dialectically, the superstructure of MMA should better reflect the interest of its fighters. In the same way, the societal forces that shape the way we think and act should also better represent the people they affect.

If we want better outcomes for students, adults, or prizefighters, we must not only change the approaches for their success but also transform the society which defines success and where these approaches are taking place.

⁂

(If you like my work, please support me on Patreon or make a one-time donation on Ko-fi. Find Southpaw at its website. Get the swag at Spring. Also check out Liberation Martial Arts Online.)